require(esm) in Node.js: from experiment to stability

More than a year ago, I set out to revive require(esm) in Node.js and landed an experimental implementation. After a lot of iteration and battle-testing, require(esm) is now unflagged across all supported Node.js LTS release lines (v20.19.0+, v22.12.0+) and has just been marked as stable. This post reflects on how it progressed from experiment to stability. In the next post, I’ll cover implementation details and the interop hatches devised for a smooth ESM transition.

A refreshed perspective on require(esm)

The previous post about require(esm) formulated an earlier theory about why it had not happened sooner, from the perspective of a contributor who did not have much experience with the module loader. Since then, iterations on require(esm) have shed more light on this topic: landing an initial implementation was the easy part, but getting it to stability required a much bigger commitment dealing with interop edge cases, backports across release lines, impact investigations, seeking consensus, finding compromises, and collaboration across the ecosystem.

To be fair, some issues stemmed from workarounds the ecosystem developed for the lack of require(esm) - a bit self‑inflicted - and the cycle could’ve been broken earlier with more investment in ESM. But Node.js is a community project powered by volunteers: there isn’t a manager who plans top-down for everyone or assigns developers to features toward a unified vision. What gets worked on is largely a consequence of the interests and bandwidths of self-coordinated contributors who happen to be active at the time. If no one steps up to keep the ball rolling, work can stall for a long time, regardless of its impact.

That said, support from the wider community - constructive feedback, positive communication, sponsorship, or just words of encouragement - can stimulate or sustain progress, especially for a component with little love but much at stake, like the module loader. In this revival, I was lucky to receive help and reviews from fellow contributors, support from friendly maintainers, and sponsorship from Bloomberg to commit more time to it. Looking back, I’d summarize why require(esm) didn’t happen earlier simply as: it takes a village, and this time the village showed up.

Should we really make require(esm) happen?

During development, a question came up: wouldn’t require(esm) remove incentives to migrate to ESM and stall the move? It’s a fair concern, but feedback from package maintainers suggested otherwise - its absence has likely done a disservice to the ecosystem, and counterintuitively, its presence may accelerate migration. This may not be obvious until you look at how migration unfolded over the past few years.

Without require(esm), ESM was an inferior shipping format

Some believed that by blocking CommonJS from loading ESM, CommonJS users would be forced to migrate once their dependencies migrated. This happened to some extent, but it turned out to be neither sufficient nor necessary. It’s common to just pin dependencies to older CommonJS versions (see the per-version download stats of a popular package on npm that has migrated to ESM, for example). In a decentralized ecosystem where projects are built from an interwoven maze of packages maintained independently, a migration plan with breaking changes as its core strategy would build up backpressure to undo those breakages by other means, and further fragment the ecosystem.

From a package author’s perspective, if CommonJS can be import‑ed by ESM and require()‑d by CommonJS, but ESM cannot be directly require()‑d by CommonJS, then CommonJS remains the common denominator for shipping with maximum compatibility, and ESM becomes an inferior shipping format on Node.js.

Workarounds inflated the cost of ESM adoption

There were still other strong incentives to adopt ESM as an authoring format: e.g. using ESM with TypeScript allows better static analysis, and it unlocks better code sharing in browsers. To make up for ESM’s weakness as a shipping format on Node.js, many packages started to transpile ESM to CommonJS:

- Packages that require bundling to run in browsers often only ship CommonJS as their runtime format on Node.js - also known as “faux ESM” (typically with ESM in

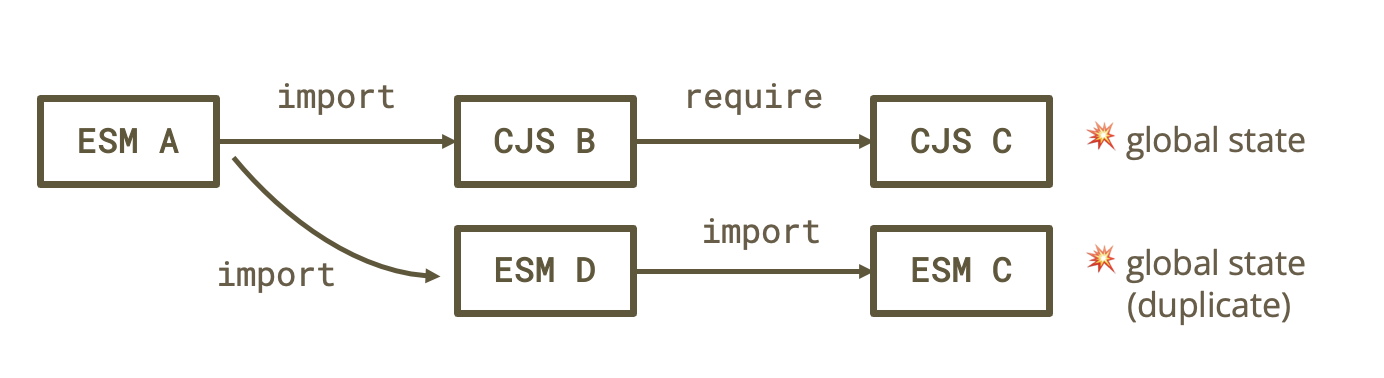

src/, transpiled CommonJS indist/). - Some packages ship both ESM and CommonJS, using

"exports"inpackage.jsonto control how it should be loaded in Node.js - also known as “dual packages”, and they risk the infamous dual‑package hazard.

So adopting ESM wasn’t just adopting the syntax: for packages that did not want the breakages, it also introduced the overhead of setting up transpilation, heavier node_modules, and the footgun from dual package hazards.

CommonJS became the path of least resistance

The mess went even further: many tools/frameworks shipped as CommonJS (even when authored in ESM) so existing plugins/users could still require() their components. To support ESM plugins/users, they transpiled user ESM on the fly and loaded it via require() from their CommonJS distribution. When that transpiled code imported external ESM packages, ERR_REQUIRE_ESM would appear unless transpilation went deeper into dependencies - fueling a vicious cycle that maintains inertia of CommonJS as the runtime format and sometimes dependence on CommonJS loader internals.

The npm‑esm‑vs‑cjs project maintained by Titus Wormer tracks ESM migration among high‑impact packages. Five years after ESM stabilized in Node.js, CommonJS still dominated as a shipping format. Even for packages already written in ESM, dual shipping was the most popular option, and shipping ESM directly remained a minority. The gap was likely even wider than the chart suggests, since it aggregates downloads across versions - now‑ESM‑only packages often still see most downloads from older CommonJS releases. In practice, most code still ran as CommonJS on Node.js, and the authoring/shipping gap kept widening.

What require(esm) unblocks

Ultimately, the lack of require(esm) created more problems for ESM adoption than it solved. Supporting it doesn’t fix every interop issue, but it would reduce friction significantly:

- Packages can migrate to and ship ESM directly without breaking or fragmenting their own ecosystems.

- Transpiling to CommonJS becomes unnecessary for many packages, reducing build complexity.

- Dual packages can drop the CommonJS distribution, lightening

node_modules. The dual‑package hazard would become a thing of the past. - Incremental upgrades in a complex codebase become more feasible.

For many maintainers, require(esm) was the last blocker to ship ESM directly. Once it landed across LTS, many popular packages started transitioning. For example, see:

What about top-level await?

As discussed in the previous post, the theoretical foundation of require(esm) is built on the ESM semantics that guarantee synchronous evaluation for ESM without top-level await. Because require(esm) needs to stay synchronous, it can’t support modules that use top‑level await. That revives an old question from 2019: does this meaningfully limit Node.js’s ESM support?

In practice, it rarely matters

Before unflagging require(esm), an analysis on the high‑impact npm packages was carried out in Sep 2024 using these scripts to gauge the impact of not supporting top‑level await from require(). At that time, among the top 5000 high‑impact packages:

- More than 3000 were CommonJS, which already couldn’t have top-level

awaitin their code. - 466 were shipped as dual and 526 were faux ESM - unlikely to use top‑level

await, since they run as CommonJS. - 559 were shipped as ESM-only. Loading them with

require(esm)revealed that only 6 of them used top-levelawait.- 3 replaced

fs.*Sync()with async variants during migration; easily reversible. - 2 used

await import('node:foo')for Node.js environment detection;process.getBuiltinModule()eliminates this use case. - 1 was minified; unclear if top-level

awaitwas necessary.

- 3 replaced

In this 5000‑package sample, only ~0.02% (1 out of 5000) might have an irreplaceable use case for top‑level await; for ~99.98%, support from require() was likely irrelevant. Meanwhile, require(esm) - even without top‑level await - could unblock ~20% of the packages already written in ESM to ship ESM directly without transpilation.

Investigation suggested that top‑level await mostly shows up in scripts and app code, but rarely in modules loaded by others. When it does show up in a library, it’s usually import‑ed within the same ESM codebase/ecosystem, which works fine. Support from require() mainly becomes relevant when ESM with top-level await is packaged and loaded by other parties, which is even rarer, so imposing some limitations there seems reasonable. require(esm) wouldn’t even be the only thing top-level await can break: its presence already changes evaluation timing and causes incompatibility with service workers. In the very rare case where an ESM containing top‑level await has to be packaged and loaded by an external party, the initialization is likely truly asynchronous, and CommonJS consumers would be better off loading it with import() instead.

Guiding principles of require(esm)

During iteration, package maintainers eager to ship ESM directly sent a lot of helpful feedback, and a few priorities emerged to guide technical decisions:

- Try not to break existing code: This makes backporting to older LTS feasible. Package maintainers rely on features only after the last unsupported LTS goes EOL, and backports can save maintainers years of compatibility burden.

- Let teams migrate at their own pace: Whether a package ships CommonJS, faux ESM, or dual packages, it should be able to migrate to real ESM without forcing its dependents (or dependencies) to move in lockstep.

- Work with bundler conventions: Bundlers have provided workarounds for years. Staying compatible helps packages that run in both Node.js and bundled environments, and adopting existing conventions wherever possible reduces friction.

- Reduce impact on leaked internals: Hyrum’s Law suggests that at scale, users depend on everything - undocumented internals or not. Given how widely the internals of the module loader have been monkey‑patched and depended on, it’s impossible to change it without breaking someone somewhere. Still, we could try to keep the surprises in undocumented edge cases, not high‑impact common paths.

- Keep performance reasonable: ESM is often slower to load than CommonJS in Node.js (e.g. 1 2). Some of this comes from semantic complexity, some from implementation. We should at least avoid introducing another significant performance gap between

require(esm)andrequire(cjs), which could again make ESM an inferior shipping format.

Backporting require(esm) to v22 and v20 LTS

For readers unfamiliar with Node.js releases: Node.js maintains multiple active release lines simultaneously. Patches are usually developed on the main branch, shipped in the “Current” release first for userland verification, before being backported to LTS. So feature availability across versions usually isn’t linear. Experimentation status isn’t strictly tied to flags or majors either - features need to be battle-tested to reach stability, so it’s common for them to be unflagged in a semver-minor release while still experimental. For LTS though, this is done with extra care, using the “Current” line as a buffer.

require(esm) was first introduced and iterated on v22 behind flags, then unflagged in v23 and iterated further with broader feedback. Along the way, updates released in v23 were also backported to v22, and require(esm) was eventually unflagged in v22.12.0.

After that, maintainers started to request a backport to v20, still an active LTS with two years of support left - if require(esm) landed there, they could drop CommonJS distributions sooner. But by then the v20 branch already lagged significantly behind the main branch, and the loader had undergone other cross‑cutting refactors/optimizations while require(esm) was developed, making backports harder. Still, the ecosystem demand made it worth a try.

My initial plan was to backport the cross‑cutting changes together to reduce conflicts, but some of them turned out to have open regressions and weren’t safe to backport. So the plan changed: only backport patches essential to require(esm), cutting down from 119 to 33 commits. Omitting cross‑cutting changes caused extra conflicts when cherry‑picking require(esm) updates, but the limited scope kept it manageable. To ensure the backport didn’t diverge by mistake, a small script to “diff the diffs” also helped.

Eventually, require(esm) was backported to v20. By then v20 was approaching maintenance mode, where volunteer efforts from releasers tend to fade away in favor of newer releases, but fortunately Marco Ippolito volunteered and released it in v20.19.0. After further verification in popular packages, it was finally marked as stable at the end of 2025.

This means package maintainers who do not support EOL Node.js versions can now simplify a package.json like this:

1 | { |

to something like this:

1 | { |

Up next

Now that we’ve discussed the high-level investigation and strategies of require(esm), in the next post, let’s look into the implementation details and the interop hatches created to enable a smooth ESM transition.